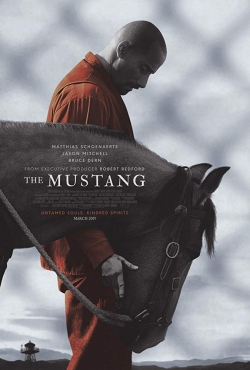

A precariously delicate balance, actress and director Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre’s debut feature film The Mustang grapples with considered focus both the taming and unbridled autonomy man and beast possess. Roman Coleman (played by Mattias Schoenaerts) has been in near isolation for the last twelve years after committing a violent beating against his wife, leaving her braindead and immobile. Silent and brooding, Roman’s cold exterior is evident in his interactions with his case worker as well as with his teenage daughter, Martha (Gideon Adlon) when she comes to visit him. Encouraged to enroll in a rehabilitation program caring for wild mustangs at the prison, the lead rancher Myles (Bruce Dern) pairs Roman with one of the horses, Marcus, in an effort to train him prior to his selling at an auctioning event. The audience learns not only about the difficulty of taming wild horses, but also about the fragile and unbound nature of man’s spirit as he integrates back into society.

Gracefully paralleled, The Mustang depicts the manner in which an incarcerated inmate and horse share common bonds. Myles’ frequent teachings of patience and self-discipline to Roman are not only as a means to successfully domesticate Marcus, but also to illuminate how to better control his volatile anger and temper. A man of few words, Roman emphasizes to his therapist that he’s simply not good with people and refuses to make an act of freedom upon her offering some semblance of control to him. Under his guise of silence, Schoenaerts does an exceptional job of exuding palpable tension, as one is never quite sure when he’s ready to lose his cool and strike. As portrayed in scenes with Marcus, the sensitive and charged behavior of Roman and his mustang are at constant interplay as the two gradually learn to read each other’s body language and intentions. Henry (Jason Mitchell), one of the more experienced mustang trainers, serves as a mentor for Roman’s volatile nature as he gradually sheds his rough and impenetrable exterior. Roman’s eventual transformation truly transpires during his visits with his pregnant daughter, initially expressing never wanting to see her again to an emotional collapse of vulnerability and wishing for forgiveness. “You think riding horses can change anything?”, she exclaims in frustration after finding out over a decade later the violence her father infringed upon her mother.

Clermont-Tonnerre teeters in her equilibrium to maintain a believable path of progress and change, often times letting predictability and bordering melodrama rein in. Roman’s outright anger and physical violations of his beast is convincing and difficult to watch, yet after an immediate existential reckoning the horse is subdued and on his side, rather than the expected loss of loyalty a wild animal might associate after being physically struck. However, most of Roman’s abrupt and explosive exchanges are convincing, further emphasizing the fate of the inmates and how it’s only a matter of seconds between their thought of violence to the actual carrying out of the crime that landed them behind bars. Despite the film’s occasional formulaic unravelling, Clermont-Tonnerre’s themes of enslavement and freedom from an individual standpoint as well as a much broader societal standpoint, make The Mustang a worthy watch and encourages us to question the often invisible shackles that we carry throughout our lives.