In the eyes of his followers (including myself), Dutch composer Arjen Anthony Lucassen is among today’s most multifaceted and original progressive metal artists. Rather than serve as the frontman for a single band, he acts as a modern day Alan Parsons, crafting dramatic, intricate, and very bombastic concepts and then employing several musicians and singers to them to life. In this way, he has more in common with, say, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice than with Russell Allen or Daniel Gildenlöw. Rarely working under his own name, Lucassen has founded several projects over the last twenty years, with his most popular and revered being Ayreon.

Between 1995 and 2008, Lucassen released seven Ayreon albums, beginning with The Final Experiement and concluding with 01011001. Like the works of Coheed and Cambria, these records served as chapters in a single grandiose sci-fi tale, with several characters (such as Ayreon and Forever of the Stars) and several locations appearing throughout. Clearly, Lucassen is tremendously ambitious and talented, and although his modesty negates his ego, his ability to create such invigorating, unique, complex, and memorable songs makes him one of the few geniuses in the field.

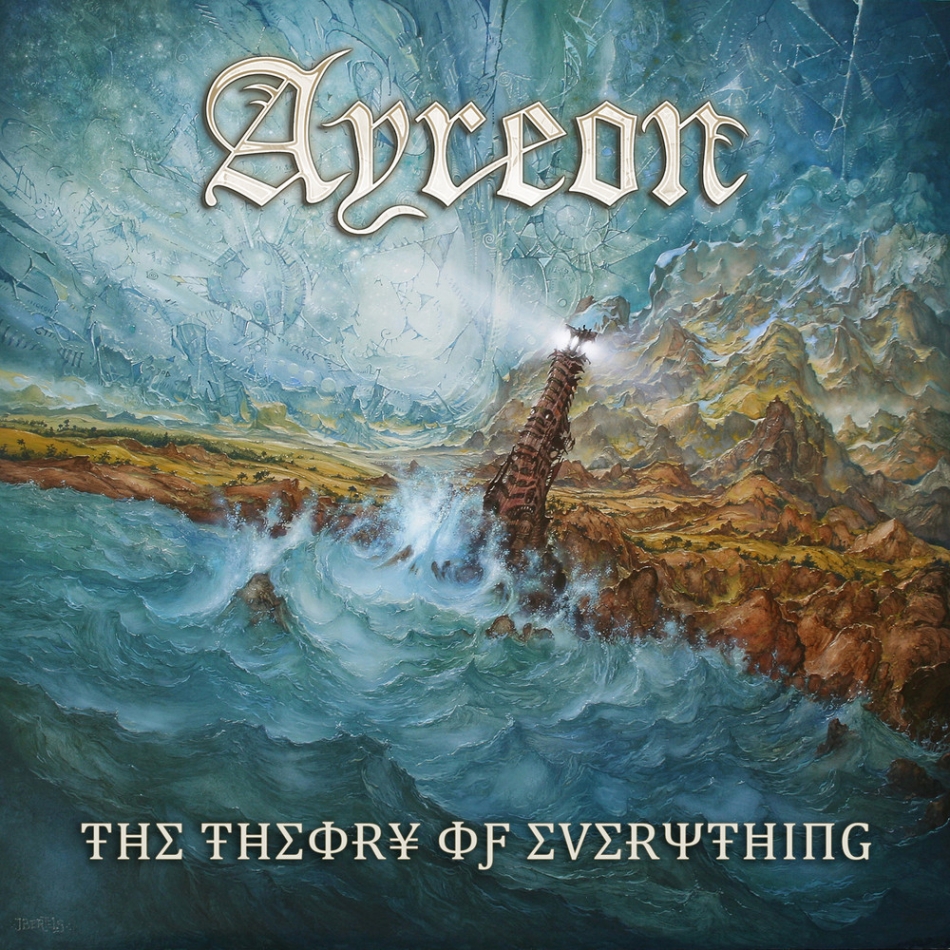

Following the release of 01011001 (which served as the final act of the storyline and was met with some [unfair] criticism for being too familiar), Lucassen decided to put Ayreon on hiatus until he felt enough inspiration to return to it. Since then, he’s released On This Perfect Day, the debut LP by Guilt Machine, Victims of the Modern Age (the second Star One record), and Lost in the New Real (his first solo album since 1994’s Pools of Sorrow, Waves of Joy). Although these records were arguably as strong as anything else he’s done (the latter even included narration from Rutger Hauer), most fans were still clamoring for a new Ayreon release. Fortunately, their prayers have just been answered in the form of The Theory of Everything. Another mind-blowing array of boisterous compositions, emotional performances, varied textures, and involving plights, it definitely earns its place alongside its predecessors. It’s not quite the best Ayreon record, but it’s damn close, and it certainly suffices as the origin of a brand new saga.

Lucassen is known for utilizing the talents of the genre’s best and brightest artists. In the past, he’s used many adored singers, including James Labrie, Devin Townsend, Mikael Åkerfeldt (Opeth), Jonas Renkse (Katatonia), Floor Jansen (After Forever) Bruce Dickinson, Anneke van Giersbergen (ex-The Gathering), Phideaux Xavier, and Neal Morse. As for past musicians, he’s featured Tomas Bodin (The Flower Kings), Derek Michael Romeo (Symphony X), Martin Orford (IQ), Clive Nolan (Pendragon), and Lucassen’s manager/partner, Lori Von Linstruth. Naturally, The Theory of Everything continues the trend, with appearances by Christina Scabbia (Lacuna Coil), Tommy Karevik (Kamelot), John Wetton (Asia, ex-King Crimson), Jordan Rudess, Steve Hackett, Rick Wakeman, and Keith Emerson helping make the album feel very well rounded.

Interestingly, The Theory of Everything is organized differently than any previous Lucassen work. Although it’s still broken up into different tracks (42 to be exact, which is a direct reference to The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy), the album really consists of four 20+ minute “phases”: “Singularity,” “Symmetry,” “Entanglement,” and “Unification.” Lucassen has said that he allowed the tracks to flow and progress naturally, adding that it’s “probably my most proggy release so far.”

Thematically, the album definitely feels like a sibling to The Human Equation, as both records concern realistic situations with characters grounded in reality (rather than the usual otherworldly sci-fi fare). In addition, both albums explore similar themes, such as love, betrayal, and forgiveness. In fact, the call and response dynamic (in which characters sing sequentially) of The Human Equation is very evident here, making it feel very different from the more singular approach of, say, The Dream Sequencer or 01011001 (in which most of the songs were sung by one character). It’s a very effective model for this narrative. Also, The Theory of Everything consists of more instrumental passages than his usual output.

As for its story, The Theory of Everything concerns an autistic savant named Prodigy, who is shunned by his peers and manipulated by his elders. At the same time, though, he’s the only person who can solve the most important equation in the history of man (hence the title). Along the way, several other characters—including his parents, rival, psychiatrist, teacher, and the girl whom he loves—play their parts in his journey. Lucassen expands upon his intentions by saying, “…it takes a look at the fine line between genius and madness, focusing on the conflicting desires of the characters and the consequences of following their passions. It's not science fiction, but a human story set in a science context.”

Opening suite “Singularity” is probably the best of the bunch, as it feels the most cohesive, seamless, and gripping. Like The Who’s Quadrophenia and Between the Buried and Me’s The Parallax II, the record starts at the end of the story with “The Blackboard,” a somber affair in which Teacher and Girl reflect on the “complex genius” of Prodigy. It displays one of the album’s main melodies, as well as sets the stage for the ensuing flashback, nicely. Afterward, “The Theory of Everything Pt. 1” consists of another recurring melody, as well as some incredible instrumentation of the usual Ayreon variety (complete with frantic rhythmic changes, awesome riffs, and a diverse palette). In fact, it’s probably one of the best instrumentals Lucassen’s ever created.

“Patterns” continues the virtuosity wonderfully, with hypnotic phrases that get under your skin (in a good way), while “The Teacher’s Discovery” features lovely acoustic guitar arpeggios underneath an intense debate between Teacher, Prodigy, and Rival. The album’s best melody comes in the form of Girl’s plea to Rival in “Love and Envy.” It’s extremely bittersweet and riveting, as is the subtle musical repetitions that surround it. “Progressive Waves” is a bit self-explanatory, I guess, but it definitely lives up to expectations, with a great sense of intricate urgency and quant folksy timbres. “Inertia” is a touching and simple interlude that leads into “The Theory of Everything Pt. II,” which adds a few new elements to the aforementioned arrangement while also giving the suite a great sense of closure.

The second “phase,” “Symmetry,” introduces listeners to Psychiatrist (John Wetton), whose authoritative voice is a welcome contrast to the more expressive singers. In “Diagnosis,” he, along with Mother and Father, discuss Prodigy’s ailments and possible treatments. The interaction between the trio during the verses and choruses is among the most forceful and catchy moments on the record (it recalls similar moments from earlier albums). “The Rival’s Dream” opens with spacey effects before woodwinds and acoustic guitar combine to create a majestic, warm sound that bleeds into ominous soundscapes. Brilliantly, Rival adds new depth to the melody from “The Blackboard” over said arpeggios. It’s fantastic.

“Surface Tension” is another exceptional instrumental dominated by flourishes of keyboard and guitar flair. The rest of “Symmetry” consists of heavy performances all around, with “Quantum Chaos” feeling like a lost track from The Flight of the Migrator amidst the histrionic declarations and affective counterpoints of its siblings. The opening of “Alive!” eerily recalls the distinct calm of classic Camel, and closer “The Prediction” acts as an appropriate cliffhanger, with Mother praising her son’s progress without knowing the underlying sinister reasons for it.

Chapter three, “Entanglement,” starts off with the delightfully melancholic “Fluctuations,” a moody minute-long gem in which sorrowful chord progressions melt over a tranquil atmosphere. As you can guess, “Transformation” finds Teacher and Prodigy discussing what they’ve accomplished with plenty of drama. It’s provides a nice contrast to the more aggressive “Collision” between Rival and Prodigy. “Side Effects” is a relatively reserved segment filled with slower utterances and betrayal. It’s reminiscent of The Dream Sequencer, and it fades into the exuberant “Frequency Modulation” expertly.

Later, “Magnetism” recalls the Celtic deceit of “Day Sixteen: Loser” from The Human Equation, as well as the overall vibe of Gazpacho’s last tour de force, March of Ghosts. The dynamic between the characters involved is exceptional, as their separate melodies blend well, and it sets up well the conflicting collaboration between Rival and Prodigy in “Quid Pro Quo.” “String Theory” is a rich orchestral interlude that includes familiar motifs. “Fortune?” ends the sequence with a great dilemma, as success leads to romantic defeat.

“Mirror of Dreams,” a peaceful yet mournful acoustic ballad, starts off the final section, “Unification.” A duet between Girl and Mother, it feels like a kindred spirit to “Valley of the Queens” from Into the Electric Castle. Next, the opening bass note of “The Blackboard” allows Teacher to discuss a safe haven for Prodigy in “The Lighthouse.” It builds nicely to a fierce debate, complete with sharp guitar riffs, while “The Parting” includes an ingenious orchestral passage in the middle of its romantically unhinged frenzy. At this point, it seems like everything is falling apart for the characters.

Fortunately, “The Visitation” finds Prodigy and Father reconciling and working together to see their dreams come to fruition. It’s an absorbing moment, for sure, with a delicate harmony serving as the crux of their chorus. Gracefully spacey effects akin to those on 01011001 are used. “The Breakthrough” is as exciting as you’d expect, with a constant explosion of technical showmanship. It serves as a great juxtaposition to the sadness of “The Note,” which begins with an altered take on “Fluctuations.” This melancholic theme continues in “The Uncertainly Principle,” which technically ends this portion of the story with a devastating plot twist courtesy of Teacher and Girl. Afterward, “Dark Energy” acts as a short bridge to two reprisals: “The Theory of Everything Pt. III” and “The Blackboard (reprise).” Here Lucassen makes the safe but smart move to ensure that his masterpiece feels like it comes full circle. It’s a perfect way to finish.

As you can probably infer already, the two elements that make The Theory of Everything stand out are its segues and conceptual continuity. More than on any prior Ayreon release, this record is packed with habitual allusions to itself, which means that it takes more listens than usual to fully appreciate how precisely arranged it is. I’ve discovered new connections each time I’ve listened to it, which is very, very cool. Likewise, the transitions between some of these tracks are awe-inspiring; they’re clever, infectious, and very moving, flowing like silk from beginning to end.

Although The Theory of Everything lacks the personality and diversity of The Human Equation, as well as the overwhelming catchiness of 01011001, it’s still a remarkable achievement. Few artists come back from a prolonged break with material that can compare to their previous glory, so Lucassen deserves accolades for doing it so well. The Theory of Everything feels perfectly situated as the third best Ayreon release, and it’s sure to top many “Best of 2013” lists come December. Rest assured, Ayreon fans, the maestro has returned with another masterpiece.