Released in 2004, Ayreon’s sixth studio LP, The Human Equation, was a benchmark achievement not only for its mastermind (Arjen Anthony Lucassen), but for progressive metal as a whole. Granted, each of its predecessors (especially 1998’s Into the Electric Castle) exemplified crucial Ayreon trademarks— hypnotic melodies, intriguing storytelling, extremely varied arrangements, and an overarching ambitious scope; likewise, the genre certainly had important concept albums before it (like Queensrÿche’s Operation: Mindcrime, Opeth’s Still Life¸ Pain of Salvation’s The Perfect Element, and Dream Theater’s Metropolis Pt. 2: Scenes from a Memory, to name a few). That said, The Human Equation trumped its five precursors in every way: the instrumentation was far more grandiose and diverse, the performances were richer and more operatic, the songs were catchier, and the plot was easily Lucassen’s most relatable and affective yet. In fact, many listeners still consider it the greatest Ayreon album to date (although its two successors, 2008’s 01011001 and 2013’s The Theory of Everything, are just below it).

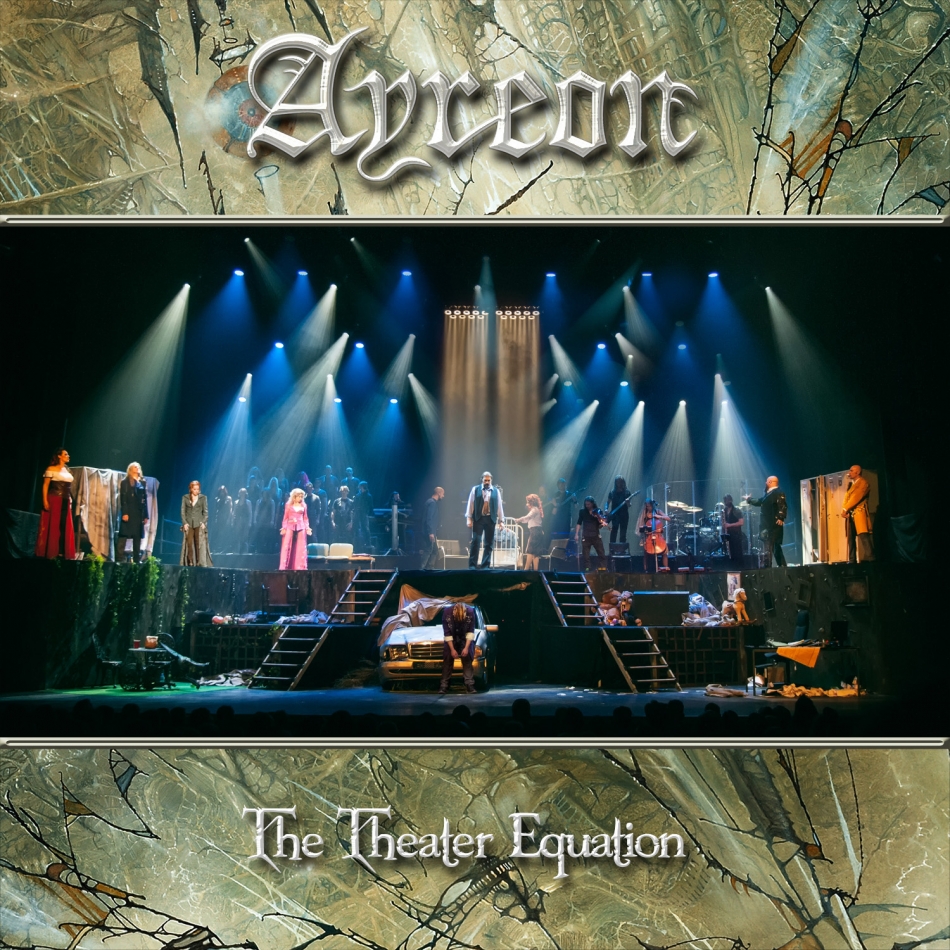

Because of its inherent theatricality, The Human Equation has always been the obvious choice for turning an Ayreon album into a stage production, and with the recently released The Theater Equation concert, fans can finally rejoice at the dream becoming a reality. Filmed on September 20, 2015 at the Nieuwe Luxor theater in Rotterdam, the show includes most of the original cast—such as James Labrie (Dream Theater) as Me (the protagonist) and Heather Findlay (ex-Mostly Autumn) as Love—as well as a nineteen-member “Epic Rock Choir,” plenty of virtuosic musicians, and subtle yet effective props, lighting schemes, and video clips. Together, these elements bring The Human Equation to life with remarkable accuracy and care while also introducing some new components that, while not unanimously successful, make the experience noticeably different from its counterpart. The Theater Equation isn’t the ideal way to experience the journey (those who’ve not heard the proper record, which is superior musically, should definitely do so first), but it’s a very cool, rewarding, and, well, surreal complement for devotees who already cherish Lucassen’s initial vision. (Rather than touch upon what makes The Human Equation a masterpiece, which I’ve already done, this review will focus on how well The Theater Equation embodies it).

Narratively, The Human Equation is quite cinematic, emotional, and absorbing. As the official press release for The Theater Equation describes it:

After a mysterious single-car accident, the victim – a man in his late 30s – lies comatose in the hospital. Before the accident he was a powerful businessman, wildly successful by any measure but also known for his cutthroat business tactics. Now he finds himself trapped in a prison that took him a lifetime to build: the prison of his own mind.

Guarding the prison are his emotions, which have taken on vivid personas inside his mind. Some are friends, some are foes, and they all have their own agendas. Some aim to trick him or dominate him, others to comfort or inspire him. But the one objective they all share is to force him to face up to the demons of his past and the deep truths about who he is and how he's lived his life, all of which he's conveniently ignored until now. Fear, Rage, Agony, Love, Passion, Reason and Pride take turns engaging the man in this emotional warfare.

Two people hold vigil at the man's bedside: his wife and his best friend. They are desperate to understand how the accident happened and to see even the tiniest sign that the man will regain consciousness. But the man's recovery is not their only concern: is it possible that he somehow found out their secret, and that the “accident” wasn't really an accident at all? Would he ever be able to forgive them?

Will the man have the strength to face the truth about himself and the ones he loves? The story unfolds over his twentyday emotional struggle with Fear, Rage, Agony, Love, Passion, Reason and Pride, in which each day of coma is represented by a song [sic].

First and foremost, the stage itself serves as a perfect backdrop for the story, as its lower half resembles the scene of the accident (complete with an actual wrecked car) and its upper half looks like a hospital (complete with morphine drip and a bed). Along the staircases that separate them are items that symbolize Me’s life, such as stuffed animals, an office desk, and plants. In addition, the lighting changes frequently seize the sentiments of the story (so everything is bathed in red for anger and love, blue for sadness, and so on), and brief scenes of nature, driving, children, and other thematic film clips play behind the bed to embellish the encapsulation. Again, it’s a relatively subdued and static presentation, but it definitely elevates the exhibition beyond mere rock show.

Of course, all of that flair would be nearly worthless if the singers/actors and musicians weren’t wholly committed, which they are. While the band resides in the background (for the most part), the vocalists move around each other and sing with complete commitment; sometimes they even interact a bit, like the multiple times the emotions slap and push Me as they confront each other. Generally, the cast nails their roles, too, with Labrie, Eric Clayton (Reason), Marcela Bovio (Wife), and Magnus Ekwall (Pride) standing out the most. Adding to their believability are their costumes, which are elegant and powerful. Labrie, in particular, looks like his character, with business attire that denotes a wealthy and commanding man who’s just left the job. As for the emotions, they wear elaborate coats, dresses, and the like to signify their larger-than-life presence. Without a doubt, these performers truly love this material.

Although The Theater Equation majorly soars, there are a few stumbles along the way. Most notably, a couple of the line-up changes don’t work as well as they should. For instance, Anneke van Giersbergen (who’s worked with Lucassen in the past, as well as with The Gathering, Devin Townsend, and Anathema) is arguably the best female signer in the genre today, but her substituting for Opeth’s Mikael Åkerfeldt (as Fear) is too jarring. Similarly, Mike Mills is very charismatic and skilled, yet he captures neither the incredible range and hellish force of Devin Townsend (as Rage) nor the quirky lunacy of Mike Baker (as Father). Perhaps this is a flaw of familiarity, but the characteristics of the originals are certainly missed.

Outside of that, there are some spoken passages (courtesy mostly of Labrie, the doctor, and the nurse) that, despite bringing more theatricality to the table, feel awkward. Along the same lines, there are several changes in terms of instrumentation and/or arrangements—including reprises not on the LP and reordered sections—that may feel equally odd to diehard fans of The Human Equation. While these innovations deserve credit for making the project stand out from its studio counterpart (after all, a simple note-for-note reproduction would invalidate the purpose of The Theater Equation), they’re still peculiar at times.

All in all, The Theater Equation is an extraordinary dramatization of one of the best progressive metal albums of all time. Its few missteps notwithstanding, the vast majority of it is impeccable, as every player goes all in to make each moment as accurate as possible. Furthermore, the set and costume designs are wonderful. Best of all, The Theater Equation allows aficionados of the record to finally see their imagined scenes play out. It’s an exceptional demonstration of how well concept albums can be brought to life, and it should pave the way for others to get the same treatment (Scenes from a Memory¸ anyone?). Let’s hope this isn’t the last Ayreon album we’ll see at the theater.

[4.5/5]