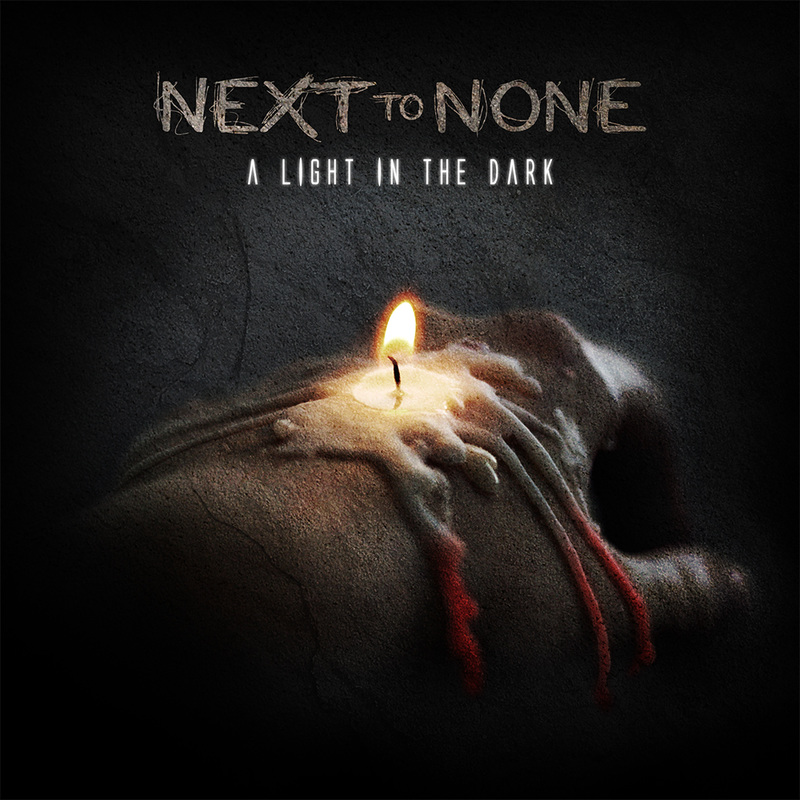

As beloved as progressive metal has become over the last few decades, there are still two major complaints that can be made against it: a lot of it sounds the same, and a lot of it favors virtuosity and theatricality over heartfelt songwriting and exclusive techniques. It seems that for every truly idiosyncratic act, there are several more that more or less fall victim to both of the aforementioned criticisms. Unfortunately, newcomer Next to None also belongs in the latter category, as its debut LP, A Light in the Dark, isn’t very diverse, memorable, or unique. Sure, it’s quite impressive for a first effort (especially considering the members’ ages), but when compared to the best work of its peers, it falls short in every aspect.

The band is comprised of keyboardist/vocalist Thomas Cuce, guitarist Ryland Jett Holland, bassist Kris Rank, and drummer Max Portnoy. Of course, Portnoy is the son of Mike Portnoy, whose work in Dream Theater, Transatlantic, Flying Colors, the Neal Morse Band, and many of other ventures has made him arguably the most famous musician in modern progressive rock. Therefore, many people probably assume that Next to None achieved its various successes due to some sort of favoritism or nepotism, and while there’s no doubt that the Portnoy name helped give them a boost here and there, there’s also no denying that Max and the rest of the teenage quartet are incredibly skilled and ambitious musicians. If there’s one thing that A Light in the Dark proves, it’s that these four burgeoning players can match the schizophrenic technicality of just about any of their older peers/influences (at just sixteen-years-old, Portnoy is likely as good as his father, and the rest of the band is equally gifted). However, what they possess in musicianship and creativity they lack in songwriting, singing, and overall originality. A Light in the Dark is a definitely a serviceable progressive metal showcase, but it contains nothing that Between the Buried and Me, TesseracT, Periphery, Mastodon, Vanden Plas, and yes, Dream Theater aren’t already doing better.

The first three tracks on the record—“The Edge of Sanity,” “You Are Not Me,” and “Runaway”—demonstrate this dissonance perfectly. After some atmospheric orchestration, Portnoy and company burst into the first song with epic intricacy (including a stop/start rhythmic pattern that’s ubiquitous within the genre). From there, the arrangement explodes into the sort of devilish complexity fans of the form have heard many times before. Likewise, both the verses and choruses of the track feel uninspired and amateurish, as if they’re the first melodies that came to their minds. The clean vocals and harmonies are too weak and, well, emo for the music, and the growls, while serviceable, feel obligatory and run-of-the-mill. Expectedly, these juxtapositions affect the other two tracks in the same ways.

Luckily, the ballad “A Lonely Walk” provides a nice change of pace, as its refined classical foundation, dynamic momentum, and poignant lyrics/vocals meld into a charmingly introspective ode. Every element, from its delicate piano notes and reserved percussion to its tasteful guitar solo and fragile vocals, is well organized, culminating in a genuinely moving piece. It’s nothing revolutionary, but it does hint at the kind of multifaceted writing the group should develop more for future releases.

Afterward, the first half of “Lost” consists of a spacey, synthesized take on Edvard Grieg’s “In the Hall of the Mountain King” (which is really interesting) before transitioning into the song itself (which is more standard stylistic fare, complete with a crazy keyboard solo). “Legacy” provides another piano ballad break from the madness, and its usage of sound effects (such as police scanners) effectively heightens the mood. Really, it evokes the sentimentality Vangough captured so well on Manikin Parade. Lastly, album closer “Blood on My Hands” is a proper tour-de-force, as it’s angrier and trickier than any of its predecessors. It allows the album to end in an epic and exhausting way, which is great.

Try as it might to avoid such classifications, A Light in the Dark offers little to elevate it beyond being another predictable progressive metal entry. Sure, the youthful singing stands out (although not always in a positive way) and some of the effects add a layer of intrigue or innovation, but for the most part Next to None does next to nothing to separate itself from the pack. This is truly disappointing, as the genre rarely features musicians this young demonstrating such breathtaking skill and drive (so one roots for them to succeed as much as possible). If they can step away from the conventions of their forebears and carve out a distinctive path with their sophomore effort, the foursome will do exactly that.